In 2005, a Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at Princeton University named Harry G. Frankfurt published a small book (an essay, really) titled On Bullshit. In this first academic consideration on the subject, Frankfurt describes bullshit as “unconnected to a concern with the truth.” Unlike a true statement (or a lie), the bullshit utterance is made “without bothering to take into account at all the question of its accuracy.” Given that I’m writing this post the morning after Super Tuesday — and given the importance of accuracy to DFS players — an exploration of bullshit seems appropriate and timely.

This is the 17th installment of The Labyrinthian, a series dedicated to exploring random fields of knowledge in order to give you unordinary theoretical, philosophical, strategic, and/or often rambling guidance on daily fantasy sports. Consult the introductory piece to the series for further explanation.

Bullshit is Like Pornography: Recognizable Yet (Almost) Indefinable

It’s not too much to say that Frankfurt’s little text changed my life when I first read it as a college student, so please excuse me if my enthusiasm reveals my fanboy status. Like the best things in life — like fantasy sports, for instance, or Shakespeare’s plays — it’s humorous, yet serious. Of all the (almost) important texts of the last decade, On Bullshit very well might be the most readable (in terms of length, style, and substance).

Gordon Pennycook, a Ph.D. Candidate in Psychology at the University of Waterloo, has continued Frankfurt’s work on the subject. Last year in the journal Judgment and Decision Making he published a quantitative overview “On the reception and detection of pseudo-profound bullshit” (the title of his article). You don’t need to read his paper if you don’t want to. What’s important for our purposes is that he puts numbers to and builds upon the ideas Frankfurt first proffered years earlier.

According to Frankfurt, the bullshitter is what he is not because he “fails to get things right.” Rather, it’s that he is “not even trying.” He is “not concerned with the truth-value” of the statements he makes. The bullshitter’s utterance “is grounded neither in a belief that it is true nor, as a lie must be, in a belief that it is not true.” Per Frankfurt:

It is just this lack of connection to a concern with truth — this indifference to how things really are — that I regard as of the essence of bullshit. . . .

For the essence of bullshit is not that it is false but that it is phony. In order to appreciate this distinction, one must recognize that a fake or a phony need not be in any respect (apart from authenticity itself) inferior to the real thing. . . . This points to a similar and fundamental aspect of the essential nature of bullshit: although it is produced without concern with the truth, it need not be false. The bullshitter is faking things. But this does not mean that he necessarily gets them wrong.

In general, I think it’s easy for us to sense when a statement we hear is deceitful — but what about a statement made by a person who doesn’t really care if what he is saying is deceitful or not? Such a statement (I believe) is harder to detect and thus much more dangerous, as is the person who issues the statement. Arguably, what made Adolf Hitler a peril to humanity was not that he lied. It was that he made inflammatory statements without caring about whether they were accurate.

Bullshit is what occurs when someone wants to speak but has nothing definitive to say. When someone wants to assert himself but has nothing on which he is authoritative. When one wishes to merge style with substance but lacks substantial thoughts or knowledge. The bullshitter is unconcerned with facts, “except insofar as they may be pertinent to his interest in getting away with what he says.” The bullshit statement is made with a desire to convince people without worrying about whether what is conveyed is actually correct.

What’s amazing about the bullshitter is that, just as his statement need not be explicitly true or false, he himself need not realize that he is a bullshitter in order to be one. In fact, the bullshitter might be the most sincere person in the world. Of course, as Frankfurt puts it in the last line of his book, “sincerity itself is bullshit.” Nate Silver, in softer language, voices the same sentiment in The Signal and the Noise:

The amount of confidence someone expresses in a prediction is not a good indication of its accuracy — to the contrary, these qualities are often inversely correlated.

All of which brings me to DFS.

The Bullshit in DFS

There’s a lot of (academically defined) bullshit in the industry, and I think it can be broken into two types. The first type is that created by those issuing content for your consumption. A lot of touts writing articles or talking on podcasts produce a lot of statements that seem as if they might be accurate — after all, they have some facts and numbers to support their position — but many of these statements at best border on bullshit, because they are made with only partial regard for accuracy.

The people making these statements probably hope that they are accurate, but they haven’t done the research to verify that the data supporting their statements is actually meaningful. They are just shooting from the hip. And, in the words of Frankfurt, “bullshit is unavoidable whenever circumstances require someone to talk without knowing what he is talking about.” At best, the people who make such statements are sloppy and careless. At worst, they are reckless and bullshitty.

I should say that I don’t think there’s bullshit at FantasyLabs. At the same time, it would be bullshit if I didn’t acknowledge that I have a vested interest in saying that we aren’t bullshitters. Arguably, what makes us truthers instead of bullshitters is our reliance on data that has been backtested. For instance, when you read an NBA article on FantasyLabs, it has the weight of our Trends and Models tools behind it, and it makes use of innovative metrics such as Plus/Minus and Bargain Rating. We care deeply about the articulation of accurate ideas. We believe that our readers and subscribers deserve not to be bullshitted.

Which brings me to the second type of bullshit, that which is intended to convince not others but oneself and which I have dubbed “self-delusional bullshit.” This is the type of bullshit produced by not touts but DFS players who believe that they have done the work to arrive at DFS truth but who haven’t.

In particular, this second type of DFS bullshit often involves one of two mistakes: either someone underfits or overfits the data so that it matches their ideas. In the first instance, someone stops short of full analysis and just hopes that their theories align with reality. In the second instance, someone has an obdurate idea of what is true and then chips away at the data to make the (unrepresentative) result of the research align with the original hypothesis. In either instance, bullshit is occurring.

My hope is that our readers and subscribers aren’t falling victim to this self-delusional form of DFS bullshit. My belief is that if people use our tools with an open-minded attitude of exploration instead of confirmation, they will avoid bullshitting themselves.

A Major League Instance of DFS Bullshit

For your edification, I have prepared an example of DFS bullshit that you might fall for either upon hearing from someone else or thinking of yourself. With the MLB regular season approaching, I thought that an example involving batters might be apt. The bullshit logic might go something like this:

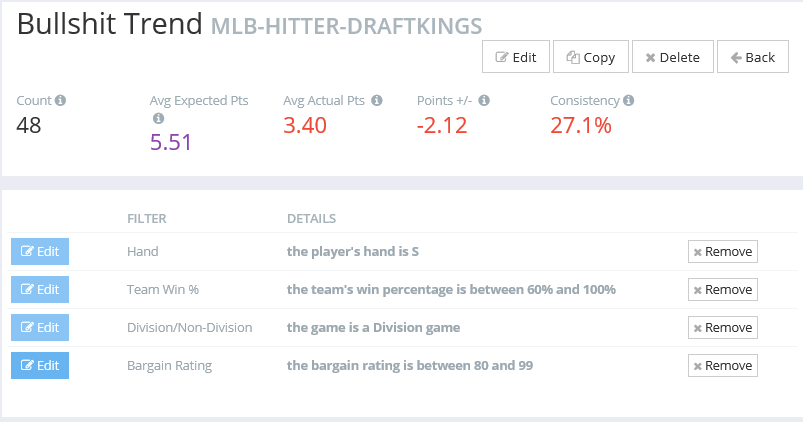

This guy is a switch-hitter, so you don’t have to worry about pitching changes. He’s a pitcher-proof hitter. Plus, he’s on a good team, so he should be able to get more scoring opportunities. He’s playing against a divisional opponent, which means that he’ll be facing pitchers against whom he has experience. And he’s available at a big discount on DraftKings relative to FanDuel, so you’re buying him cheap. He’s a must-play DFS option in this slate.

That sounds like decent logic — but it’s bullshit. For one, it’s way too specific. Looking at relatively discounted switch hitters on good teams playing against division opponents might be a decent idea if you are chasing Black Swans, which are by definition rare and overly particularly, but it’s not a good idea as a general trend, since the sample of past players is likely to be small and possibly unrepresentative.

Secondly and more importantly, the data that we have shows that players who match this trend have not done well historically.

What makes the example statement a bullshit utterance is that it is made with no regard for what the performance data of past players actually indicates. Granted, it’s a small sample, so maybe the idea of targeting really cheap switch hitters on good teams playing against division opponents will be proven to be very successful over the next decade — but what’s concerning is that the speaker doesn’t even mention that players in that situation have historically done well (or poorly). Rather, the speaker hasn’t even done the research.

Inauthenticity vs. Inaccuracy

The hallmark of bullshit is inauthenticity, which should not be confused for inaccuracy. Remember, sometimes bullshit can be accurate, even if it uses a haphazard process. Likewise, sometimes (though hopefully not too often) the most careful projections can lead to inaccurate outcomes. That happens.

Inaccuracy is a constitutive part of any predictive endeavor. That’s a part of the process. In DFS, when our lineups are thwarted by outcomes our process did not anticipate, we mustn’t automatically believe that we have been engaging in bullshit. Instead, we must return to the data and examine our logic.

Upon reflection, if you realize that you erred, you adjust your process. Or if you realize that you didn’t err but instead merely experienced the randomness and downside that accompanies the business of acting on the evidence of the past, then you maintain your process.

Of course, to improve your process and ensure that you’re not a DFS bullshit victim you must be willing to do the self-evaluative postmortem in the first place. Refusing to do that work is the biggest bullshit move of them all.

———

The Labyrinthian: 2016, 17

Previous installments of The Labyrinthian can be accessed via my author page. If you have suggestions on material I should know about or even write about in a future Labyrinthian, please contact me via email, [email protected], or Twitter @MattFtheOracle.

Thanks to RotoViz editor Charles Kleinheksel for calling my attention to Pennycook’s article on pseudo-profound bullshit, and special thanks to professor and FantasyLabs reader Dr. Jeffrey Michael Clair (drbubba) for eliciting some of the ideas herein via our email exchanges.