In college, I majored in English, Biology, and Chemistry because I had no idea what to do with my life. I particularly loved Organic Chemistry and even took an extra graduate-level course in it as a junior, just because. For that class, I did a research project on the chemical and molecular mechanisms through which Pfizer’s moneymaker Viagra works. It was fascinating. I even considered applying to Ph.D. programs in the field with the intention of becoming a drug designer for a biotech company — I thought that it would so cool to create a drug for a particular illness — but my mind was quickly changed when my professor told me about the streamlined process by which big pharma discovers drugs. He called this process “shotgunning.” At the time, I thought it sucked and was utterly uncreative. Now, I think that it might be the key to your fantasy success.

This is the fifth installment of The Labyrinthian, a series dedicated to exploring random fields of knowledge in order to give you unordinary theoretical, philosophical, strategic, and/or often rambling guidance on daily fantasy sports. Consult the introductory piece to the series for further explanation on what you are reading. Just think of this as the DFS version of The Neverending Story.

The Non-Art of Creating a Drug

In The Bed of Procrustes, his book of philosophical and practical aphorisms intended to highlight our self-delusional world of “backward fitting,” the theorist Nassim Nicholas Taleb provides this insight near the beginning of his prelude:

Pharmaceutical companies are better at inventing disease that match existing drugs, rather than investing drugs to match existing diseases.

Taleb’s sentiment might seem extremely cynical, but it’s not entirely incorrect. Whenever a new disease is discovered, many pharmaceutical companies (per my college professor) will immediately test their large inventory of “existing drugs” to see if any of them effectively treat the disease. And by “existing drugs,” I mean “random compounds that the companies have created but never mass produced or used as a treatment for any diseases in the past.”

How is it that these pharma enterprises just happen to have a large inventory of “existing drugs” that are entirely useless and unprofitable up until the moment when they are matched with a disease? Shotgunning.

As explained to me over a decade ago, here is how pharmaceutical companies “create” drugs. Whereas in the old days, when scientists labored for years attempting to design a particular drug with a precise shape and perfect functionality to treat a specific disease, nowadays scientists will quickly analyze a disease. They will think about the shape and functionality that the disease’s “perfect theoretical drug” might have. They will think a lot about the various chemicals that, when mixed together in various combinations and proportions, may have a decent chance of producing a compound that isn’t quite the perfect theoretical drug but might be close enough in shape and functionality.

And then they just throw those very reactive chemicals, in various combinations and proportions, into many industrial tanks and see what happens. In the end, in each of those tanks thousands of unique compounds will be created, all of which will be tested as a possible treatment for the target disease. The scientists don’t care which one of the new compounds ends up being close to the perfect theoretical drug. They just hope that one of them is.

If that happens, then the compound is mass produced, marketed as a miracle drug painstakingly designed by brilliant scientists, and then sold in bulk for billions of dollars.

And the thousands of compounds that don’t match are warehoused for the day when they can be tested, as Taleb might put it, on diseases that haven’t been invented yet.

As you can see, for pharmaceutical companies, the key to making money isn’t in designing the perfect drug. It’s in systematically yet randomly creating thousands of compounds, one of which might be good enough.

Shotgunning Isn’t Just For Weddings, Weed, & Beer

The DFS applications of the pharmaceutical approach of shotgunning seem apparent.

The huge industrial tanks are your typical guaranteed prize pools. The chemicals put into the tanks are players. And the various combinations and proportions of the chemicals are lineups.

The thousands of unique compounds represent the range of possible outcomes for all the lineups entered into a GPP.

And the one compound that ends up being a near match for the perfect drug? That’s the nearly perfect GPP-winning lineup that ends up making you a lot of money.

How are you to determine the chemicals to put into tanks? Fantasy Labs. In our Trends section, you can use our data to backtest an almost limitless number of ideas.

For instance, if you wanted to know how a player with a high Bargain Rating can be expected to perform on DraftKings, you could run a backtest and would find that historically, a player with a Bargain Rating of 80 to 100 has averaged 2.04 fantasy points more than his salary-adjusted expectation, per our exclusive Plus/Minus metric:

Clearly, players with high bargain ratings could be candidates for use in GPPs — and with the ability to analyze many DFS ideas you can start to identify the types of players who may have an elevated chance of paying off for you.

And then how are you to determine the combinations and proportions of chemicals to put in the tanks? With our Player Models and new Lineup Tool.

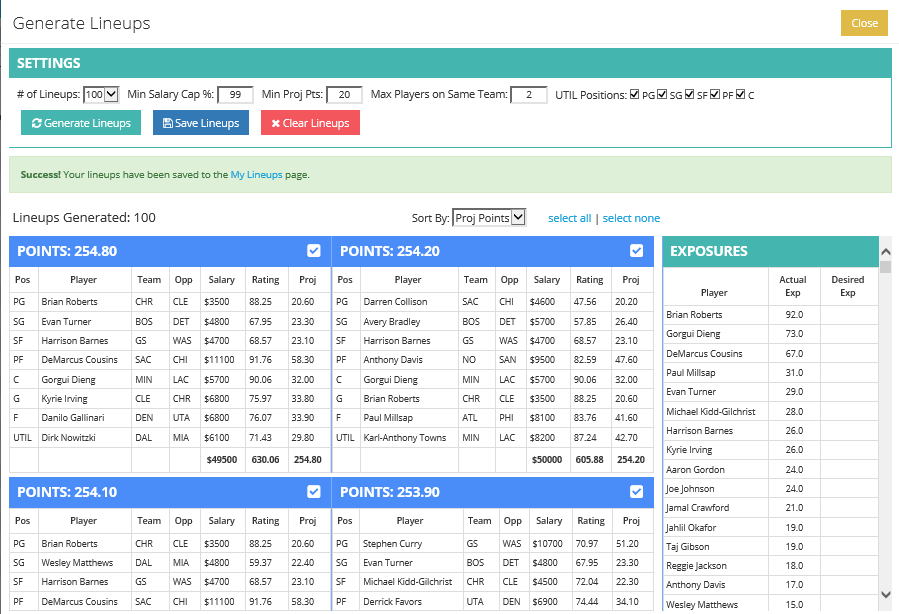

With any model of your choosing — the Simpleton’s Model, perhaps — you can easily use the new lineup generator to shotgun hundreds of lineups in a matter of seconds:

And once you have generated and saved your lineups, you can easily export them (hundreds at a time) out of FantasyLabs and import them into DraftKings, where they can be entered into the big industrial tanks of GPPs.

And then, thanks to a combination of luck and skill, one of your shotgunned lineups just might produce a GPP-winning outcome.

Using the FantasyLabs tools, you can easily become the DFS equivalent of a modern-day pharmacological chemist.

Perfection is the Enemy of Good Enough

Taleb would probably dislike the aphorism that serves as this section’s title, but it nevertheless contains applicable truth.

Like a pharmaceutical company “designing” drugs, you should never become too focused on any given lineup when creating entries for a GPP. Instead, you should focus your attention on the types of players you want and then create, through a streamlined shotgunned process, as many distinct lineups as possible with those players.

The key is not to let your desire to create the perfect theoretical drug prevent you from shotgunning a drug that is good enough to make you money.

With our new DFS lineup builder tools, shotgunning just got a lot easier.

———

The Labyrinthian: 2016, 5