I first learned about Gaia theory in a biology class during my first semester of college. The professor who introduced me to this theory was one whom I never appreciated. I found him needlessly aggressive in class. It turns out, he was also misinformed. What he was calling “Gaia theory” was really chaos theory.

This is the 43rd installment of The Labyrinthian, a series dedicated to exploring random fields of knowledge in order to give you unordinary theoretical, philosophical, strategic, and/or often rambling guidance on daily fantasy sports. Consult the introductory piece to the series for further explanation.

Chaos Theory: Initial Conditions Are Everything

Gaia theory and chaos theory are similar in that they both seek to explain a highly interconnected and dynamic world — but the former focuses more on the larger nature of relationships while the latter deals with the micro-mechanisms of those relationships.

Specifically, chaos theory is a mathematical field that studies dynamic systems, the actions of which are inordinately dependent on and sensitive to initial conditions. Per Nate Silver’s The Signal and the Noise, the systems to which chaos theory apply have these properties:

-

The systems are dynamic, meaning that the behavior of the system at one point in time influences its behavior in the future;

-

And they are nonlinear, meaning they abide by exponential rather than additive relationships.

The theory was first expounded by a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Edward Lorenz, who in the early 1970s was attempting to develop a program that could forecast the weather using a computer that was probably bigger than my refrigerator.

(As you might expect, I wrote that last sentence immediately after visiting my refrigerator. Initial conditions are everything.)

Lorenz’s Pet Bug: Randomness

Eventually, after Lorenz’s weather program produced wildly divergent and unexpected forecasts using what was believed to be the same data set and code, Lorenz realized that the erratic simulations had been the result of a small decision: One of the technicians had changed the code by rounding up at the third decimal place. Once Lorenz realized that even the seemingly inconsequential was immensely consequential, chaos theory was born.

Here’s what I find especially delicious: Lorenz himself is the embodiment of the theory he articulated. If not for his technician’s small decision, Lorenz would’ve been an entirely different person with a different career path. He might’ve been just a regular MIT professor whose name students wouldn’t have been able to recall 20 years after they took his class. Instead, he became the Father of Chaos Theory.

He became the guy who realized that a butterfly flapping its wings in one part of the world can cause a hurricane in another part of the world a few weeks later. He became one of the first academics truly to grasp the significance of randomness.

Realizing that a small change in initial conditions can result in drastically different outcomes is no small feat. That’s basically discovering how life works. (It’s also discovering that the Back to the Future movies, though entertaining, are total bullshit.)

Learning What I Didn’t Know

This article was originally intended to be published a week ago. Most of what you just read I wrote last Friday morning. It wasn’t published last week because of a few reasons, one of which was that I still wasn’t 100 percent sure what I was talking about — which hasn’t stopped me from publishing some pieces before . . . (he said with good-natured self-awareness) . . . but it did stop me in this case.

Last Thursday, a FantasyLabs subscriber asked me to help him sort out what was going on with a trend. As someone who works for FL, I am (or at least pretend to be) something of an authority on our suite of tools. I looked at his situation, thought I knew what was going on, and gave him an answer.

It turns out, I was wrong. I had no idea what I was talking about. I thought that I was talking about Gaia theory, but it was really chaos theory.

When I discovered what was really happening, I was excited. Honestly, it was maybe the most excited I’ve been about something to do with sports since the Cowboys decided to be wise and pass on Ezekiel Elliott at pick No. 4 . . . never mind.

Adjusted Baselines: Initial Conditions Are Everything

Let me walk you through the situation. See if you can discover what’s happening.

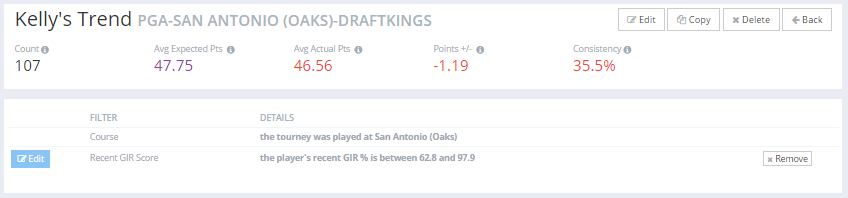

Last week, FL contributor Kelly McCann published a piece in which he used our PGA Trends tool to look at golfers who had good Recent Greens in Regulations (GIR) Scores at the San Antonio Oaks Course. What follows is a recreation of the trend Kelly created (the numbers are now different because they include the data from last weekend’s tournament):

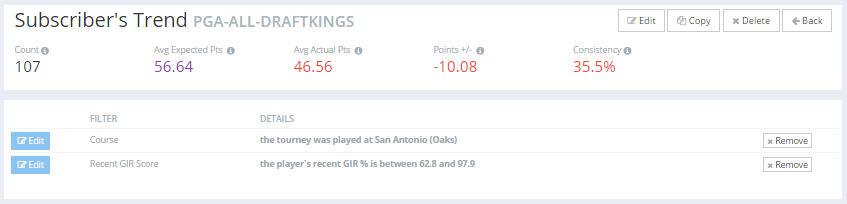

Now, using the exact same criteria, the FL subscriber tried to recreate that trend. Here’s what he got:

Wow. The trends are ostensibly the same, right? Both of them have the same GIR Score criteria, and both look for golfing performance at the SA Oaks Course. Both trends seemingly match for the same cohort of golfers, given the precise correspondence we have in count and average expected points.

Also intriguing is the correspondence in Consistency, despite the vast difference in Plus/Minus. The twinned Consistency signifies either two possibilities:

- At least on SA Oaks, underperforming salary-adjusted expectations by about one fantasy point isn’t all that different than underperforming by 10 fantasy points, since seemingly the exact same golfers did both. In other words, the difference between disappointing and devastating is almost nonexistent, at least in this scenario.

- We have a Lorenzian bug. That’s a possibility.

And what intrigues me most about these two trends is that, despite having the same cohort of golfers, they have drastically different average expected points, a fact that results in their having divergent outcomes.

Why is this the case? Chaos theory.

The initial conditions for the trends might seem similar, but they aren’t. The baselines are utterly dissimilar. They have been adjusted. And, in retrospect, given that our PGA product is overseen by Colin Davy, whose Twitter handle is @AdjBaseline, I should’ve understood the core difference between these two trends much faster than I did.

All Courses vs. SA Oaks

I’ve written before about what is included in our Plus/Minus metric. It is basically just actual production minus expected production. Of course, given the current context, that definition of Plus/Minus is deceptively simple.

The concept of actual points is easy to grasp. In the trends above, the actual points are identical. But the concept of expected points can give us problems. How exactly are expectations determined?

For PGA, expectations are generally determined by the total sample of golfers and salaries in our database. If a golfer has a $7,500 salary in one slate, the expectations for him will be determined by the prior performances of all previous golfers who have had $7,500 salaries in all previous slates. I’m simplifying slightly — but that’s the basic idea.

For 99 percent of all PGA scenarios, that’s how Plus/Minus is determined. That’s what we see in the Subscriber’s trend: 56.64 average expected points (based on past salaries and performances at all tournaments) and 46.56 average actual points (based on past salaries and performances at SA Oaks).

Of course, for that remaining one percent of PGA scenarios, we see something very different. The Plus/Minus in Kelly’s trend does not have expected points that are based on all tournaments. Rather, it uses as its baseline only the data from past tournaments at SA Oaks.

This difference is incredibly significant. In Kelly’s trend, the expectations have nothing to do with how golfers do on all the courses in the world. The expectations are determined by only how golfers have done on one course: 47.75 average expected points — based on just the past salaries and performances at SA Oaks.

What Does All of This Mean?

That functionality (of which most subscribers are unaware) is immensely powerful. To be able to use our PGA Trends tool to adjust expectations on a course-by-course basis is simply astounding.

On the one hand, a course-specific Plus/Minus is based on a relatively small sample of past salaries and performances and thus might be a little too uncertain to trust for cash games. That’s an important caveat.

On the other hand, a course-specific Plus/Minus (with all of its subtleties and potentially noiseless signals) could provide subscribers with a massive edge in tournaments.

I don’t think that it’s a coincidence that within the last month FL co-founder Peter Jennings (CSURAM88) won the DraftKings Fantasy Golf World Championship for the RBC Heritage slate or that one of our subscribers won the DK PGA Millionaire Maker for the Masters slate. We have incredible PGA tools that can be leveraged to great success.

I believe that our course-specific Plus/Minus function is perhaps the most unknown and undervalued of those tools.

How Did We Get Here? (Part I)

How did Kelly and the subscriber get two different trends even though they essentially created the same trend?

Initial conditions.

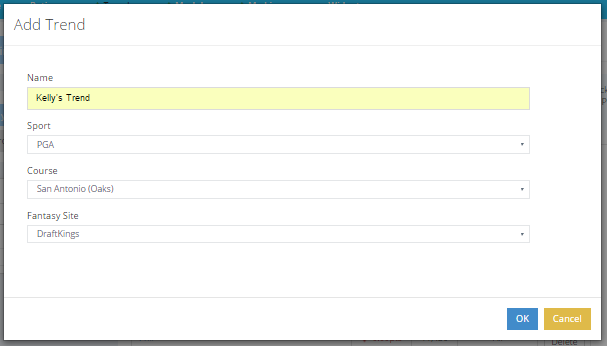

When Kelly created his trend, he specifically designated SA Oaks as the course to which he wanted all performance calibrated:

Do you see that? SA Oaks was built into Kelly’s trend as an initial condition and a constitutive component.

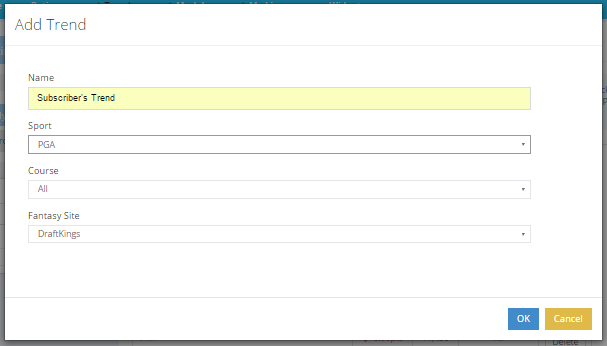

In our subscriber’s trend, SA Oaks was not a part of the initial conditions:

Instead of creating a trend exclusively centered around SA Oaks, the subscriber (by going to “Player Filters” and then “Course”) added the SA Oaks criteria to the trend after it had been created.

It’s incredible that such a small difference at the beginning could result in such a large difference at the end.

And, to be clear, I’m not saying that the subscriber did anything wrong or that there’s one preferable method to constructing this trend. The point here is that there are multiple ways to construct this trend, each of which has its own expectations, merits, and uses.

Up until a week ago, I didn’t know that. (And, since I pretend to be an authority, I probably should’ve known that.) I bet that you probably didn’t know that either.

Now we all know.

How Did We Get Here? (Part II)

That’s really the question, isn’t it? And the answer has everything to do with chaos theory.

How did we get to the point where I’m writing and you’re reading the 43rd Labyrinthian? When I wrote the first piece in this series a little over three months ago, I had been at FL for about a week. To say that I had a limited idea of what I was doing was generous. (Just ask my editors. Better yet, don’t.)

I had a vague idea of what this series might be . . . but not really. The entire series has been determined in part by the initial conditions: I was a guy who was just writing and working his way into something that he hoped would made sense. I was imagining that the series would be the thing that I would do while I figured out what I was going to do.

Instead, the series has simply become the thing that I do. In that regard, it’s very much like life. And if you were to ask my wife, she would say that this series has become my life.

Each piece in the series has been incredibly dependent on the initial conditions under which the pieces were started. The material I read, the music I listened to, the conversations I had, the food I ate, the deadline I had, the sleep I didn’t get — all of those had an immense impact on the content and shape of each piece in this series.

Under the initial conditions, I never imagined that this series would be longer than 10 pieces. I now feel pretty confident that we’ll get to 50. After that, who knows?

I can’t say where the center is in relation to where we are. I can’t say how much longer we will walk till we get there. All I know is that with each step, we are likely both closer to the end — and farther.

———

The Labyrinthian: 2016, 43

Previous installments of The Labyrinthian can be accessed via my author page. If you have suggestions on material I should know about or even write about in a future Labyrinthian, please contact me via email, Matthew@FantasyLabs.com, or Twitter @MattFtheOracle.